The Untapped Potential of Plug and Play Solar

America's rooftop solar systems are oversized, expensive, and over-engineered. It doesn't have to be this way.

The traditional residential solar model in the US features large, grid-connected systems that cover most or all of a home's energy needs, requiring professional teams to handle permits and utility interconnection as well as skilled crews for installation that permanently mount the modules and their racking into roofs. The systems are major capital investments for homeowners, costing $25k on average, with a majority of systems requiring financing. Furthermore, the size of the installations often requires homeowners to spend thousands on costly electric panel upgrades. While equipment prices have fallen, the total cost of installing residential solar has risen since 2021 due to labor and permitting “soft” costs.

That model is exclusionary. As solar systems are major modifications to residential structures, only homeowners are able to install them, locking renters out of solar’s lucrative bill savings and tax credits. Systems are often priced too high for low or fixed-income homeowners to afford, even with financing. Moreover, utilities face increased expenses to manage solar exports from net-metered systems, 'leading to higher energy bills for disproportionately lower-income customers without grid-connected solar. In California, over 20% of energy bills are subsidies for net-metered homes to maintain grid connections.

There is a considerably less-engineered and cheaper alternative to America’s residential solar model that avoids heavy capital investment whilst opening solar up to new customer bases: Plug-and-play solar systems.

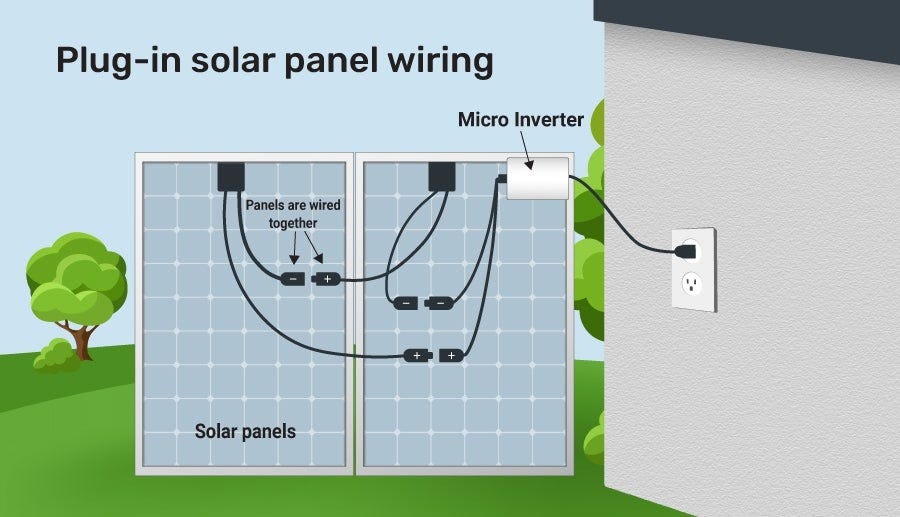

Plug-and-play systems are sold as DIY kits that include small arrays of solar modules connected to a microinverter. The microinverter converts the DC power generated by the modules into AC power compatible with the electric grid. Each kit has an extension cord that plugs directly into a wall outlet. This setup allows the generated power to reduce the home’s electricity consumption by counterbalancing energy use. Unlike traditional grid-connected solar systems, plug-and-play solar cannot export power to the grid, instead offsetting electricity consumption as it occurs. Plug-and-play systems also tend to be smaller than traditional installations, as they must have a low enough wattage to connect to 120-volt AC wall outlets without overloading circuits. Because the systems only offset usage, there’s no need to dedicate breaker space on an electric panel to them, and the grid does not need to upgrade to accommodate their export.

Renters who have not been able to pursue solar can do so with plug-and-play. The kits cost as little as a few hundred dollars. There’s no need for a professional installer as their assembly is as easy as putting together Ikea furniture and plugging in a cord. The buyers simply purchase the modules, and depending on the specifics of their kit, string together the modules, screw them to a mounting frame, place them anywhere with sunlight, and plug them in. Because the modules are mounted temporarily by the purchasers, they’re not modifications to structures. The versatility of the systems allow them to be moved seasonally or even throughout the day to maximize production.

While plug-and-play solar has expanded dramatically in Germany in recent years, it faces significant challenges in the United States due to a near-complete absence of a legal framework. This gap has led to a gray market where dangerous plug-and-play systems that lack the anti-islanding features needed to prevent backfeeding into the grid during blackouts, as well as excessively large systems that cannot be accommodated by a standard 120-volt outlet, are sold alongside reputable products on online marketplaces like Amazon.

To underscore the regulatory ambiguity the technology faces in the Pacific Northwest, when asked about plug-and-play legality, the Oregon Building Codes Division responded that they don’t believe plug-and-play solar kits are “installations” regulated under their respective electrical codes as long as the equipment complied with accredited laboratory electrical safety tests. When the Washington Department of Labor and Industries (which oversees building codes) was asked about the technology, they responded that solar mounted in any manner, even plug-and-play, qualified as an “installation” that required electrical inspections and compliance with the National Electric Code (NEC).

That discrepancy in determining whether plug-and-play systems fall under the NEC shapes their legality. The NEC mandates that solar systems incorporate grounding, rapid shutdown disconnects, and dedicated circuits. These requirements prevent plug-and-play solar from being allowed without a professional electrician assigning it a dedicated circuit on the home electrical panel, thereby undermining the technology’s affordability and DIY appeal.

Additionally, utilities in Oregon and Washington also have the right to disconnect service to homes they believe are engaging in unsafe activities. Pacific Power or Portland General Electric could use that authority to demand that none of their customers use plug-and-play solar for fear of grid backfeeding, banning systems equipped with anti-islanding features under blanket policies.

Furthermore, local siting is oriented around the traditional residential solar model. While Washington has no law overruling local ordinances on residential solar siting, Oregon’s residential solar law, ORS 215.439, requires local governments to make solar permits ministerial only if the modules are “parallel to the slope of the roof,” and “do not increase the footprint of the structure,” precluding balcony or wall-mounted plug-and-play solar. Local governments are not obligated to permit it at all, let alone ministerially or “by-right.” Consequently, a neighbor’s complaint regarding a balcony-mounted installation could prompt a local government to issue a cease-and-desist letter to the owner.

This year, Utah became the first state in the US to pass legislation regarding plug-and-play solar. HB 340 S1, passed unanimously in its 2025 legislative session, included three major provisions that ensure the safety and formalization of these systems and establish a framework for their legal operation.

It established a standard definition of plug-and-play systems, limiting their size to 1.2 MW to prevent overloading of circuits.

It ensured that plug-and-play systems allowed by state law are required to have anti-islanding features that prevent power export during outages, avoiding backfeeding into the grid.

It prevented utilities from banning their customers from using said systems.

While the legislation established a valuable framework for safer market adoption, key regulatory gaps remain. Utah’s HB 340 S1 won’t cause a mass adoption of plug-and-play overnight. The bill did not stipulate that municipal governments permit the technology, it did not reform the state’s version of the NEC to establish greater permissiveness for small solar systems without dedicated circuits, nor did it clarify whether plug-and-play is an “installation” or not.

However, the legislation was a crucial first step in formalizing the technology and setting standards for product sellers, thereby enabling prospective buyers to procure the systems safely, creating a permission structure for them to challenge their local governments' ambiguous regulatory stances. Furthermore, by clearly distinguishing plug-and-play systems, the bill provided guidance to state regulators for rulemaking that could result in the systems not being considered “installations” regulated under the NEC.

Looking ahead, states such as Oregon and Washington have an opportunity to build upon Utah’s model. Those states should amend their local siting laws to allow mounted plug-and-play solar as a matter of right, update their specialty electric codes to clearly delineate when NEC requirements apply, and prevent restrictive practices like landlord bans on portable solar setups. By addressing these gaps, those states can foster a renewable energy landscape that enables both homeowners and renters to benefit from affordable solar power.

This needs a nice big discussion of $/KWH. Incentives drive outcomes. Average price of electricity in Germany is over double that in the US.

On factor that is often glossed over is that traditional solar is only ever cost effective with both federal and state tax credits.

If it’s not illegal to sell DIY panels without built-in islanding features you know people will install without and endanger linesmen.